Nations across Canada are asserting jurisdiction over education in innovative and powerful ways. Through mechanisms like self-government agreements and modern Treaties, Nations are revitalizing languages, implementing land-based learning, and taking control over their education systems and institutions. At JFK Law, we understand the importance of self-government over education to Nations who are working towards a better future for generations to come, and we wanted to highlight some exciting examples of Nations doing so.

Sectoral Self-Government Agreements

Through negotiation with Crown governments, self-government agreements provide for the exercise of law-making power by First Nations and are based on a recognition of First Nations’ inherent right to self-government. Approaching self-government by sector, for example by focusing just on education, can simplify negotiations and accelerate the exercise of First Nations jurisdiction. Self-government agreements can also be tied to important funding commitments on the part of the Crown in order to support the delivery of education services. Below are examples of education self-government agreements from across the country:

Mi’kmaw in Nova Scotia

In Nova Scotia, education is delivered to participating Mi’kmaw Nations through Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey (MK), a corporate body that acts as a collective voice for Mi’kmaq education. The  Mi’kmaw people are signatories to the Peace and Friendship Treaties. In 1997, MK was set up pursuant to An Agreement With Respect to Education in Nova Scotia, a self-government agreement negotiated with nine of the 13 Mi’kmaw Nations in Nova Scotia.[1] Three more Nations later joined the Agreement. The Agreement recognizes the jurisdiction of Mi’kmaw Nations over primary, elementary, and secondary education on reserve and with management responsibility for post-secondary education programs. MK is governed by a Board of Directors made up of the Chiefs of the participating First Nations.

Mi’kmaw people are signatories to the Peace and Friendship Treaties. In 1997, MK was set up pursuant to An Agreement With Respect to Education in Nova Scotia, a self-government agreement negotiated with nine of the 13 Mi’kmaw Nations in Nova Scotia.[1] Three more Nations later joined the Agreement. The Agreement recognizes the jurisdiction of Mi’kmaw Nations over primary, elementary, and secondary education on reserve and with management responsibility for post-secondary education programs. MK is governed by a Board of Directors made up of the Chiefs of the participating First Nations.

MK schools feature language immersion, cultural integration, land and sea based learning, and other programs. They also administer a funding program for community-based projects that strengthen Mi’kmaw cultural identity as well as preserve and revitalize the Mi’kmaw language. MK prides themselves in high graduation rates and attendance rates.[2]>/sup> 83% of First Nations students in Nova Scotia are educated in MK schools, and MK now operates schools in twelve of thirteen Mi’kmaw communities.

Self-Government Agreement- Anishinabek Nation

Ratified in 2017, the Anishinabek Nation Education Agreement is a self-government agreement between Canada and 23 Anishinabek First Nations that recognizes First Nation jurisdiction over education from junior kindergarten to Grade 12 both on and off-reserve. It is the largest education self-government agreement in Canada. The agreement provides funding for the operation of the Anishnabek Education System/Kinoomaadziwin Education Body (AES), a system that operates parallel to provincial education systems. Participating First Nations have full control over how the education funding is allocated, and funding can be used for a variety of purposes including educational programs and services that incorporate Anishinaabe culture, language, history, knowledge and values, and post-secondary funding.[3] The Agreement ousts certain provisions of the Indian Act related to education and recognizes participating First Nations law-making power over education through the AES. Other First Nations can join the agreement in the future if they wish.

education from junior kindergarten to Grade 12 both on and off-reserve. It is the largest education self-government agreement in Canada. The agreement provides funding for the operation of the Anishnabek Education System/Kinoomaadziwin Education Body (AES), a system that operates parallel to provincial education systems. Participating First Nations have full control over how the education funding is allocated, and funding can be used for a variety of purposes including educational programs and services that incorporate Anishinaabe culture, language, history, knowledge and values, and post-secondary funding.[3] The Agreement ousts certain provisions of the Indian Act related to education and recognizes participating First Nations law-making power over education through the AES. Other First Nations can join the agreement in the future if they wish.

The structure of the AES is set up so that each participating First Nation has law-making power and authority over education from junior kindergarten to Grade 12 through a Local Education Authority. Each participating First Nation that belongs to a Regional Education Council that provides opportunities for networking and determining education priorities, as well as electing candidates to sit on the Kinoomaadziwin Education Body Board of Directors. The Participating First Nations work together through the Kinoomaadziwin Education Body to support the delivery of education services and to centrally communicate with Ontario in relation to education.

The 23 participating First Nations also chose to be a part of the Master Education Agreement with Ontario, which establishes a relationship between Ontario and the participating First Nations as well as supports student success and well-being in both the AES and the provincial education system. Part of this agreement is aimed at developing curriculum related to First Nations history and culture to be taught in the provincial education system.

The Master Education Agreement also has a strong emphasis on simplifying processes for Anishinabek students transferring between the two systems.

In 2019, the Reciprocal Education Approach was developed in partnership with First Nations and school boards across all of Ontario, and is aimed at removing barriers for First Nation students transitioning between school systems in Ontario in order to improve access to education.

The Anishinabek Nation Education Agreement is available in a plain language version here.

The Master Education Agreement is available in a plain language version here.

First Nations Education in British Columbia

Cowichan Tribes, Lil’wat Nation, ʔaq’am, and Seabird Island on July 11, 2022 signed self-government agreements regarding education on their lands with Canada. This means that the First Nations now have recognized law-making authority over their education systems (K-Grade 12) including authority over teacher certification, school certification, graduation requirements, curriculum, and course approvals.

The First Nations Education Authority (FNEA) was also established as an independent body that assists First Nations in BC to assume jurisdiction over their K-12 education systems on their land and capacity development, with two directors appointed by each First Nation to the FNEA. To support the negotiation of self-governance agreements in education, Canada has transferred funding to eligible First Nations at an amount that covers 100% of the cost of developing a self-governance agreement, up to a maximum of $8,000,000 per year. Now that four First Nations are implementing self-governance agreements, the federal government is providing $10.6 million over 10 years to support governance and education.

Cowichan Tribes is the largest First Nation in British Columbia, with a total population of over 5,000 individuals. Members approved the draft protocol on January 8, 2022, after 15 years of negotiation with Canada. As laws are developed for education, community consultation and approval will be central to the process moving forward. Currently, a Community Education Authority is being formed for effective education governance practice. This structure will be reviewed and ratified by the community. Currently, Cowichan Tribes’ Education and Culture Committee has recommended that Cowichan Tribes establish a new legal entity, a Community Education Authority (CEA), to operate, administer, and manage its education system.

Cowichan Tribes is the largest First Nation in British Columbia, with a total population of over 5,000 individuals. Members approved the draft protocol on January 8, 2022, after 15 years of negotiation with Canada. As laws are developed for education, community consultation and approval will be central to the process moving forward. Currently, a Community Education Authority is being formed for effective education governance practice. This structure will be reviewed and ratified by the community. Currently, Cowichan Tribes’ Education and Culture Committee has recommended that Cowichan Tribes establish a new legal entity, a Community Education Authority (CEA), to operate, administer, and manage its education system.

Líl̓’wat Nation has over 2,000 members, most living near Mount Currie, British Columbia. With education from daycare to adult and post-secondary in their community, Lil’wat Nation has long been engaged in directing their education system. Their band-run school has been in operation since the mid-1970s. Today, Ucwalmícwts Immersion education is available for children from pre-K to grade 7, and Ts̓zil Learning Centre offers local adult education to Nation members and the broader community.[4]

Chief Dean Nelson highlights the importance of self-governance in certifying teachers. He notes that some community members have strong cultural and spiritual knowledge, which wouldn’t be recognized in a provincial system that prioritizes specific credentials. Such educators may be better suited to progress cultural and language teachings in Líl̓’wat schools. Overall, Chief Nelson recognizes that control of education equates to “control of our own lives.”

ʔaq’am is a smaller community with fewer than 400 registered members, which aims to teach using Ktunaxa methods, with Ktunaxa people as teachers and education professionals. The ʔaq̓amnik School currently offers the British Columbia curriculum and hires British Columbia certified teachers, with an additional cultural program featuring Ktunaxa language and tradition. The ka kniⱡwi·tiyaⱡa, “our thinking” or strategic plan describes education and learning as a core value, and effective self-governance as a key goal. Education encompasses lifelong learning and includes both sides of the coin: career preparation, and culture and language. Asserting, reclaiming, and using education jurisdiction is a specific objective of the strategic plan.

Former Seabird Island Chief Clem Seymour says that education jurisdiction is important to bring back teachings and understandings about how we take care of one another. He recognizes that the whole community should be involved in raising a child and sees education jurisdiction as a way to get back to that. The community of over a thousand people works together for these goals.

There is also explicit connection between the Seabird Island schools to residential schools. Because some of the teachers are second generation residential school survivors, they focus on providing students with context about who they are and where they come from – something they themselves did not get in the residential school system. Seabird Island Chief and Council on August 16th 2022 gave final approval to officially enact their Education Law.

Modern Treaties

Modern treaties recognize Indigenous rights and articulate relationships between Indigenous Nations and Canada. Modern treaties are comprehensive, constitutional documents that cover a wide range of subject areas and thus take lots of time and resources to negotiate. Education can be one area over which Indigenous jurisdiction is recognized through modern treaties.

wide range of subject areas and thus take lots of time and resources to negotiate. Education can be one area over which Indigenous jurisdiction is recognized through modern treaties.

James Bay Northern Quebec Agreement – Nunavik

In Nunavik, self-governance in education is included in the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (“JBNQA”), the first modern treaty in Canada. The JBNQA established Kativik Ilisarniliriniq, the sole provider of educational services in Nunavik, and recognized the jurisdiction of the board over elementary, secondary and adult education. In Nunavik, Inuktitut education spans from early childhood through life. The JBNQA explicitly directs Inuktitut to be the language of instruction, as well as requires cultural programming and teacher training about language, Inuit culture, and pedagogy.

The modern treaty model reflects a constitutional approach to recognizing Inuit sovereignty and establishing an education system founded on language and culture. The JBNQA is also an example of a much more broadly implemented model, as all Nunavik children can access Inuktitut education up until Grade 12. The Kativik School Board has also developed attractive and effective online education tools for teaching Inuktitut and Inuit culture, accessible through an online platform.

First Nation School Board

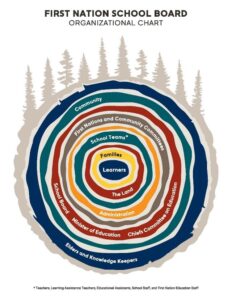

In Yukon, the First Nation School Board (FNSB) enables Yukon First Nations to share authority with the Government of Yukon in order to deliver public-school education across Yukon.[5] These schools teach a version of the British Columbia school curriculum that is tailored to reflect Yukon First Nations worldviews. The FNSB runs ten schools across Yukon which are open to all students in Yukon. The FNSB approach shares decision-making power between the Chiefs Committee on Education, the Yukon Ministry of Education and elected schoolboard trustees in order to serve all students in Yukon and promote reconciliation through a strengths-based, community-centered approach. The FNSB is funded by the Government of Yukon.

schools teach a version of the British Columbia school curriculum that is tailored to reflect Yukon First Nations worldviews. The FNSB runs ten schools across Yukon which are open to all students in Yukon. The FNSB approach shares decision-making power between the Chiefs Committee on Education, the Yukon Ministry of Education and elected schoolboard trustees in order to serve all students in Yukon and promote reconciliation through a strengths-based, community-centered approach. The FNSB is funded by the Government of Yukon.

Additionally, the Yukon Education First Nation Education Directorate (YEFNED) operates parallel to the FNSB with a focus on improving outcomes for Indigenous children in Yukon by providing wrap-around services.[6] YEFNED is led by the Chiefs Committee on Education alone and is funded through Jordan’s Principle funding and Indigenous Services Canada.

Indigenous Schools in Urban Centres

Indigenous Schools in Urban Centres

Some Indigenous schools operate within provincially funded education systems rather than pursuant to First Nations jurisdiction alone. These schools are particularly important for Indigenous children living in urban centers. An example of such a school is the Kâpapâmahchakwêw – Wandering Spirit School in Toronto, which is operated by the Toronto District School Board. Kâpapâmahchakwêw is a kindergarten to Grade-12 school that provides Indigenous focused education, including courses in Anishinaabemowin, and First Nations, Métis, and Inuit courses.

Treaty Right to Education

The educational clauses contained in the numbered Treaties have established educational policy such as education services and a fiduciary obligation to provide educational services. During Treaty negotiations, it was understood by the parties that education is necessary for the well-being of First Nations.

Alberta Context

Amiskwaciy Academy is western Canada’s first urban Aboriginal high school, located in Treaty 6 territory. The name comes from the Cree word for “Beaver Hills House” – amiskwaciwâskahikan, the name Cree people used for Fort Edmonton. Amiskwaciy Academy was created through a partnership between the Edmonton Public School Board and the Alberta government, and was developed in consultation with Elders and the Aboriginal community. It was opened as a pilot project in 2000, to better meet the educational needs of Aboriginal students living in an urban environment. The school welcomes all students who have a desire to understand the values, traditions, and cultures of Aboriginal peoples.

AWASIS Program – “awâsisak – Little sky beings that are loaned to us in the most sacred way”. The Awasis Program is the Edmonton Public School Board elementary program that provides students with Cree Language instruction and cultural teachings and activities. Some of the Cree Language and cultural activities include Cree Language curriculum of study, Cree prayer, seasonal Feasts, Awasis Day celebration, Metis jigging at Guitar and Fiddle, and field trips to cultural sites.

Conclusion

Through sectoral self-government agreements, modern treaties, the expression of numbered treaties, school boards and public schools, there are many opportunities available to Indigenous Nations and organizations to express their jurisdiction over education. JFK Law LLP is present and responsive to these developments and is eager to support First Nations in their efforts to ensure that Indigenous youth have access to education that meets the needs and priorities of Indigenous peoples.

——————————-

[1] Government of Canada, “Agreement with Respect to Mi’kmaw Education in Nova Scotia – Backgrounder.”

[2] Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey, “About Us.”

[3] Kinoomaadziwin Education Body, “The Anishinabek Education System.”

[4] The Líl̓’wat Nation education jurisdiction website includes links to the Law-making Protocol, Summary Canada-First Nation Education Jurisdiction Agreement, and Agreement to Amend the Education Jurisdiction Framework Agreement: Líl̓wat Nation, “Education Jurisdiction Information”, online: <https://lilwat.ca/engaged/7564-2/>.

[5] First Nation School Board, “Home.”

[6] Yukon First Nation Education Directorate, “About Us.”

Authors:

Isabel Klassen-Marshall, and Ashley Wehrhahn (Summer Students, 2024)