Since the BC Supreme Court released Cowichan Tribes v. Canada (Attorney General), 2025 BCSC 1490, in August 2025 declaring that the Quw’utsun (Cowichan) Nation holds Aboriginal title to lands at Tl’uqtinus on the Fraser River in Richmond, public discourse has been dominated by concern about private property rights, and misconceptions and misinformation have run rampant. The gap between what the decision says and how it’s being portrayed in the media and by some politicians is significant, creating unnecessary fear and confusion, and concerningly, a rise in anti-Indigenous racism.

This blog post aims to clarify what the Court’s decision says about private property and to correct some of the misinformation that has been spreading. Our firm has been following this case closely and wrote about it when the decision was first released. Our firm continues to comment on this decision in newspapers, on the radio (on CBC when the decision was released and this week as well as on CKNW) and at conferences on developments on Aboriginal and Indigenous Law. The Court’s decision is subject to appeals by all parties, meaning that the judge’s findings of fact and conclusions on the law are under dispute by the appellant parties (the Quw’utsun Nation, Canada, BC, Musqueam Indian Band, and Tsawwassen First Nation). In this post, we focus on what the judge found, and on clarifying the law, in order to push back on fear, confusion, and racism in the public dialogue about this case.

Property Rights 101: Aboriginal Title and Fee Simple

Generally, commentary about the Cowichan decision should be approached with a critical eye: the decision is 863 pages long and deals with a number of intertwined, complex issues. It cannot easily be summarized into a single issue or soundbite.

However, much of the confusion about the Court’s decision in this case also stems from a misunderstanding of what Aboriginal title is and how it relates to the fee simple ownership that most of us are familiar with. These are two different types of property rights, and understanding the distinction is essential to understanding what the Court decided.

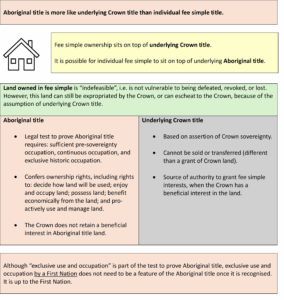

Aboriginal title is a unique right held by an Indigenous collective that is grounded in the fact that Indigenous peoples occupied and governed their lands before European settlers arrived. It includes the right to exclusive use and occupation of the land, the right to determine how the land is used, and the right to enjoy the economic benefits of the land. Since 1982, Aboriginal title has been protected by Canada’s Constitution.

Fee simple, on the other hand, is the most common form of property ownership in Canada. It’s what most people think of when they think about “owning” land. Fee simple ownership is derived from the Crown’s asserted ownership of land. Fee simple ownership entitles the holder—whether a private individual, a corporation, or a government—to exercise essentially every conceivable act of ownership over the land. Here is a visual to help illustrate this concept:

Aboriginal title and fee simple ownership are two distinct forms of property rights. Historically, in British Columbia, the Crown did not recognize Aboriginal title; rather, it assumed that it held title to the land and proceeded to grant those rights to settlers. This led to the exclusion of Indigenous peoples from their own territories throughout the Province. Cases such as the court case brought by the Quw’utsun Nation are about addressing these historical wrongs by the Crown and determining how these overlapping rights should be reconciled today.

What the Decision Actually Says About Private Property

- The Court Declared Aboriginal Title

The Court issued a declaration of Aboriginal title over a portion of the claimed area (around 40%). A declaration is a legal remedy that allows a court to clarify the state of the law, without ordering any specific action or damages. The area over which Aboriginal title was declared overlaps with lands held as fee simple title by the City of Richmond, Canada, Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, and private landowners and businesses.

- Cowichan Nation Did Not Seek to Invalidate Private Property Titles

The focus in the media and by politicians has been overwhelmingly on private property owners, with little acknowledgment that Indigenous peoples also hold property rights.

Here’s what’s getting lost in the public discussion: the judge found that the Quw’utsun Nation had their lands taken from them and have been excluded from their own territories for decades. In this case, the Quw’utsun Nation never asked the Court to invalidate the titles held by individual homeowners or private businesses and never tried to get those lands back. The Nation’s case is not about taking land from individual private property owners in the claim area.

The Nation has emphasized that they intentionally did not bring this case against individual private landowners or private businesses. In doing so, the Nation has in fact taken a respectful and responsible approach, aimed at reconciling their interests and those of the individual titleholders. Their case focused on holding the Crown accountable for its actions, not on challenging individual British Columbians.

Contrary to what’s being said by much of the media, the Court’s ruling does not “erase” private property. It does not mean that private property owners in the area over which the Court declared Aboriginal title no longer own their lands. Private fee simple interests continue to exist on these Aboriginal title lands.

The remedies the Quw’utsun Nation sought—and received—were only against lands held by governments: the federal government, the City of Richmond, and the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority. These are the only lands where the court declared the fee simple titles invalid.

- Aboriginal Title Does Not Displace Fee Simple Title

The Court also did not hold that Aboriginal title automatically or necessarily displaces fee simple title. Instead, the Court clarified that Aboriginal title and fee simple interests can coexist, though their exercise may sometimes conflict. What the decision makes clear is that reconciliation is needed between these overlapping interests, and it is British Columbia’s constitutional obligation to advance that reconciliation.

The Gaayhllxid • Gíihlagalgang “Rising Tide” Haida Title Lands Agreement is an excellent example of a negotiated agreement that addresses the coexistence of Aboriginal title and fee simple lands. While that agreement affirms Haida Aboriginal title throughout Haida Gwaii, under the agreement the Haida also consent to existing fee simple titles, fully protecting those private property rights into the future.

Modern treaties also offer helpful lessons on Aboriginal ownership of land. Briefly, through the negotiation process for modern Treaties, Treaty Nations acquire treaty settlement lands in fee simple. These Treaty Nations may then grant property interests in their lands to third parties, but the lands retain their status as treaty settlement lands. Mortgage lenders are familiar with situations where a Nation owns the entirety of its Treaty lands in fee simple, and the Treaty Nation’s land laws apply to its lands.

The Historical Context: Understanding the “Land Question”

- The Historical Background

Contrary to what it may seem, and contrary to much of the media reporting, this isn’t a new issue that suddenly appeared with the Cowichan decision. The “Land Question” is a longstanding issue dating back to European settlement in British Columbia. Indigenous peoples occupied and owned their lands long before settlers arrived and Indigenous property rights were recognized by British colonial law. These rights were continued under Canadian law as Aboriginal title.

Although colonial governments understood that Indigenous people had rights in the land, their policy for most of British Columbia was to not negotiate treaties to address those rights. Rather, colonial governments simply acted as if they held all the land rights, freely granting them to settlers. This policy created the overlapping interests we’re grappling with today, including in the Cowichan case.

- The Specific History at Tl’uqtinus

The specific history at Tl’uqtinus makes the injustice particularly stark. Colonel Richard Moody was the Crown official tasked with setting aside reserve lands for Indigenous people at their settlements. Instead of fulfilling this responsibility, Moody covertly sold some of these lands at Tl’uqtinus to himself as a land speculator. The Province of British Columbia is the source of all the Crown-granted fee simple titles on what the Court has now declared to be Cowichan Nation Aboriginal title lands. As the Court found: “the situation we find ourselves in today is the product of the Crown’s failure to address the Cowichan claim, historically, and in modern times” (at para. 3550).

Addressing the Misinformation

Since the decision was released, several false claims have been circulating and need to be corrected.

Quw’utsun Occupation of Ancestral Lands

The City of Richmond’s briefing note to private property owners claimed that the Quw’utsun Nation “abandoned” their ancestral lands 150 years ago. The Court found otherwise. After hearing evidence over more than 500 days of trial, the Court found that the Cowichan continued to occupy their village through the 1870s and probably continued to use the site for fishing into the early 20th century. The Court stated that the Quw’utsun Nation “maintained a substantial connection to their land, which they have not abandoned today” (at para. 1597).

Moreover, this claim ignores the impacts that colonial policies had on Indigenous communities: the overturning of traditional economies, bans on traditional governance structures, the prohibition on Indigenous people hiring lawyers and the State’s efforts to erase Indigenous languages and cultures through residential schools, among other policies, resulted in the displacement and ultimate exclusion of Indigenous peoples from their own lands.

Notice of Proceedings

There have also been complaints about private landowners not being served with formal notice of the trial through the court process. However, this issue was raised in 2017, and the Court declined to order Quw’utsun Nation provide formal notice because it was not seeking relief from the private landowners. The Court did state however, that any of the defendants—Canada, BC and Richmond—were free to provide informal notice to private landowners if they wished (at paras. 23-27). They chose not to do so. In other words, it was always within Canada’s, BC’s and Richmond’s power to inform private property owners about the ongoing litigation with the Quw’utsun Nation. They decided against it.

Extinguishment Argument

Some have suggested that different legal arguments could have protected private property interests. For instance, Richmond argued at trial that the granting of fee simple titles extinguished Cowichan’s Aboriginal title. This argument was unlikely to succeed. The Supreme Court of Canada established almost 30 years ago that provinces do not – and have never had – the constitutional authority to extinguish Aboriginal title. The Court reiterated this in the Cowichan decision: “The Province has no jurisdiction to extinguish Aboriginal title” (at para. 3000).

Finally, private property interests have not been invalidated, and the Quw’utsun Nation has not sought to displace private owners. Any suggestions in the media and by some politicians that the Quw’utsun Nation will seek remedies against private landowners is highly speculative and would be contrary to the Nation’s clear and deliberate approach in the litigation. These suggestions detract from the very real and inevitable question of how to provide justice and achieve reconciliation with Indigenous Nations, while providing clarity to British Columbians who now hold private ownership interests in those lands.

What Happens Next and Moving Forward

All parties have indicated they will appeal the decision. An appeal to the BC Court of Appeal, and potentially further to the Supreme Court of Canada, will take years. We’re looking at a lengthy process before there’s final legal clarity on many of the issues raised by this case. During this time, legal questions will continue to be clarified and refined.

However, the Court stated in no uncertain terms that litigation is not the way to resolve these complex issues. The judge stated that litigation is “the antithesis of a healing environment” (at para. 3727) and made strong statements about the Crown’s duty to negotiate in good faith with the Cowichan Nation to reconcile the overlapping interests. Negotiated agreements can bring clarity, certainty, and equity for all parties in ways that court battles simply cannot. Modern Treaties and the Haida Rising Tide Agreement noted above are excellent examples of what can be achieved through negotiation. British Columbia needs more of these negotiated solutions.

This decision is a call for the long-overdue work of reconciliation. British Columbia needs more recognition of Indigenous rights and more certainty through negotiated agreements. The hard work of answering the Land Question—the question of how to reconcile Aboriginal title with other interests in the land—cannot be avoided. As the Court held, it is BC’s constitutional obligation to advance reconciliation.

Reconciliation requires good faith from governments and understanding from all British Columbians. Inflammatory rhetoric and misinformation campaigns work against reconciliation and create unnecessary division and fear. The path forward is through negotiation, not fear. If property owners are anxious about what this case means, they should direct those concerns to the provincial government and urge the government to come to the negotiation table in good faith. That is where the real work of reconciliation will happen, and where solutions for everyone—Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike—can be achieved.