The Federal Court sides with Nunavut Inuit and upholds the Nunavut Agreement in overturning a decision of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to allocate Nunavut offshore commercial fishing licences to southern non-Inuit interests.

In Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated v Canada (Fisheries and Oceans), 2024 FC 649 – a landmark decision released on April 26, 2024 – the Federal Court quashed a decision by the Minister of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (“DFO”) on the basis that it was unreasonable in light of the Nunavut Agreement. This case is consequential not only for Nunavut Inuit, but it also signals to government, and all Canadians, the pivotal, everyday role politicians and bureaucrats have in diligently implementing treaties and their requirement to do so.

Factual Background: The Nunavut Agreement requires DFO to pay “special consideration”

Since time immemorial, Inuit have been stewards of arctic waters and resources in the territory now known as Nunavut. Inuit continue to be the vast majority of Nunavut’s growing population.

Nunavut is home to Canada’s largest coastline where all but one community are coastal. Nunavut’s waters are unique in having a concentration of high-quality, high-value fisheries all in a relatively sensitive arctic marine environment. Fishing is acutely important to the vitality of Nunavut communities. Communities are isolated with no outside connecting roads, they often lack a local economy and suffer from disproportionate impoverishment. These factors make Inuit uniquely positioned to benefit from and to develop a sustainable fishery in Nunavut waters.

However, Inuit have struggled to access any commercial fishing opportunities in their offshore waters, which are among the most valuable. Southern Canadian interests have historically held the majority of the commercial fishing licenses in Nunavut offshore waters. As a result, the significant benefits extracted from Nunavut fishing – such as related revenues, infrastructure, employment, and training – are lost to benefit the economy of other jurisdictions and not Nunavut Inuit.

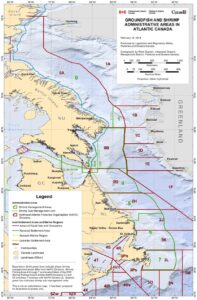

The signatories to the Nunavut Agreement (1993) recognized that fishing is an integral part of Inuit culture and key to developing a sustainable Nunavut economy. It’s against this backdrop that the signatories established section 15.3.7 in the Nunavut Agreement to guide DFO decision-making with the intent to redress this inequity by dis-entrenching non-Inuit southern interests in Nunavut fisheries in support of a diversified and self-sustaining Nunavut-based economy. Section 15.3.7 provides that framework by requiring that government “recognize the importance of the principles of adjacency and economic dependence of communities…on marine resources” and give these principles “special consideration” in allocating licences.[1] The principle of adjacency recognizes that communities closest to a resource are generally best suited to benefit from that resource, including economically. These principles apply holistically to promote a fair distribution of licences in what’s known as Nunavut Adjacent Waters – a designated area in Nunavut’s offshore that is particularly rich in Greenland Halibut (also called turbot) and Northern Shrimp.

The signatories to the Nunavut Agreement (1993) recognized that fishing is an integral part of Inuit culture and key to developing a sustainable Nunavut economy. It’s against this backdrop that the signatories established section 15.3.7 in the Nunavut Agreement to guide DFO decision-making with the intent to redress this inequity by dis-entrenching non-Inuit southern interests in Nunavut fisheries in support of a diversified and self-sustaining Nunavut-based economy. Section 15.3.7 provides that framework by requiring that government “recognize the importance of the principles of adjacency and economic dependence of communities…on marine resources” and give these principles “special consideration” in allocating licences.[1] The principle of adjacency recognizes that communities closest to a resource are generally best suited to benefit from that resource, including economically. These principles apply holistically to promote a fair distribution of licences in what’s known as Nunavut Adjacent Waters – a designated area in Nunavut’s offshore that is particularly rich in Greenland Halibut (also called turbot) and Northern Shrimp.

Despite its clear terms and independent efforts by Inuit to gain access, in the decades since the Nunavut Agreement was signed, the DFO has not effected a fair distribution of licences among commercial fishing enterprises as required by section 15.3.7. Nunavut holds approximately 76% of the commercial fishing license allocations in Nunavut’s adjacent waters. Other jurisdictions with an offshore – such as the maritime provinces or British Columbia – typically enjoy upwards of 85% of license allocations in their adjacent waters.

Nunavut interests have raised these issues directly with DFO and in a number of independent reviews, including senate committees and in court.[2] Nigel Banks, an emeritus professor of law at the University of Calgary, provides an excellent summary and case commentary on efforts to address Nunavut adjacent water inequity through the history of court challenges, which can be read here.

In July 2021, a critical opportunity arose for the DFO Minister to implement the Nunavut Agreement. Clearwater Seafoods Limited Partnership (“Clearwater“) was seeking the Minister’s approval under the Fisheries Act to issue a series of licences to FNC Quota Limited Partnership (“FNC”) and Premium Brands Holding Corporation (“Premium”), including licences with significant allocations in Nunavut adjacent waters. FNC is owned by several Mi’kmaq nations and had acquired Clearwater’s shares and was to solely hold all licences previously held by Clearwater in Atlantic Canada, including the Nunavut adjacent licences, which formed a small part of the overall transaction.

Inuit conveyed to the Minister that the decision was a rare opportunity for the DFO to finally redress the chronic inequity Nunavut adjacent waters through implementing section 15.3.7, particularly given Nunavut adjacent licences so rarely come up for sale or reissuance due to their limited number and high value.

However, ultimately the Minister decided to issue the licences to FNC and Premium (the “Minister’s Decision”), indicating that Nunavut interests “already hold very significant shares in the two areas for which Clearwater has licences”, the licences were “already purchased”, and that there was “no regulatory role for the Minister” to play.

QIA and NTI filed to judicially review the Minister’s Decision in Federal Court in September 2021, and Clearwater and FNC joined alongside the Minister as respondents. The decision was released on April 26, 2024. Canada has not appealed the decision.

The Law: treaties require diligent implementation in Crown decision making

On April 26, 2024, the Federal Court released its decision to quash the Minister’s Decision and sent it back to the Minister for reconsideration on the basis that it was unreasonable, saying:

the [Minister’s] Decision was not justified in relation to the legal constraint of the Nunavut Agreement nor was it justifiable, transparent, or intelligible in its analysis and determination of special considerations within the meaning of Article 15.3.7 and the honour of the Crown.[3]

The Federal Court makes significant findings on the nature of treaty implementation in the routine decisions of the Crown as it relates to the Honour of the Crown and reconciliation, as well as the specific meaning of section 15.3.7 of the Nunavut Agreement.

Broad Crown discretion can be curtained by the terms of a treaty. Treaty implementation must be informed text of the treaty as a whole and the principle of the Honour of the Crown (which is always at stake when the Crown engages with Indigenous peoples.[4] In this case, the Federal Court confirmed that while the Minister has broad discretion to allocate licences and quota under the Fisheries Act, this discretion is significantly constrained as a result of the Nunavut Agreement.[5] It is precisely this constraint on discretion, combined with and informed by the Honour of the Crown, that heightens the government’s requirement to diligently implement treaties.[6]

What is an unreasonable decision should be determined in light of the treaty.[7] In finding that the Minister’s Decision was unreasonable in this case, the Federal Court made a number of important determinations, which are summarized below.

The terms of a treaty must be meaningful in decision making. As treaties are constitutionally protected agreements, meaningful decision making invoking the treaty must include more than a restating of principles and requires actual engagement with the circumstances.[8] In this case, the term “special consideration” in section 15.3.7 means there is a guarantee that the Minister will pay “particular and appropriate attention” to the principles of the Nunavut Agreement in determining a fair distribution of licences in light of the circumstances.[9] The Minister’s Decision was unreasonable in that a fair distribution was considered only in broad terms without addressing the special considerations of adjacency and economic dependence as well as the delays in upholding these principles.[10]

The decision maker must grapple with the evidence relating to the fulfilment of treaty terms. In implementing the Crown’s obligations under treaties, it must seek pathways forward to do so and take account of the evidence before it.[11] A decision maker should demonstrate that consideration.[12] In this case, the Federal Court found that the Minister had a “heightened responsibility” to analyze and engage with the evidence, and that level of engagement was required to demonstrate how special considerations were determined under the Nunavut Agreement, given it is a constitutionally protected treaty requirement and it is a requirement of the Honour of the Crown.[13]

Reconciliation is an implied term of treaties.[14] Reconciliation can be used as a means of measuring how successful the Crown has been in interpreting and implementing the terms of treaty in its decision.[15] This is because modern treaties are intended to “smooth the way to reconciliation” in a way that advantages the continuity, transparency and predictability of Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations in the mainstream of the legal system.[16] Here, the Federal Court noted that the DFO appeared to provide more written justification on the economic importance of the transaction to FNC than to Inuit treaty rights and interests, despite the requirement for the Minister to give special consideration to the economic dependency of Nunavut interests on the fisheries.[17] The Federal Court found that the lack of engagement between Inuit and other Indigenous interests in light of reconciliation further demonstrated the unreasonableness of the Minister’s Decision.[18]

In sum, this case is a turning point for Inuit in seeking equity, a “fair distribution”, in Nunavut’s adjacent waters within the meaning of the Nunavut Agreement. The consequences of such has tangible, on-the-ground impacts to the vitality of Nunavut communities.

This court decision also carries pointed jurisprudential value for treaty signatories seeking meaningful and timely implementation of their treaties. That is that government must be alive to their obligations under treaty, and their corresponding duty to implement their terms diligently. Governments that do not do this are vulnerable to having their decisions being challenged.

What’s Next?

The Minister’s Decision is back before the Minister to redetermine whether to issue some or all the licences originally held by Clearwater to FNC and Premium, including the licences in Nunavut’s adjacent waters, and under what terms and conditions considering the court’s reasons.

With the benefit of the Federal Court’s clear guidance, both NTI and QIA are hopeful that the Minister’s reconsideration will allow for Nunavut Inuit to access Nunavut’s adjacent fisheries in a manner that is fair and comparable to the share enjoyed by southern jurisdictions. You can read their joints statements in response to the Federal Court’s decision on QIA’s website linked here.

[1] Section 15.3.7 reads: “Government recognizes the importance of the principles of adjacency and economic dependence of communities in the Nunavut Settlement Area on marine resources, and shall give special consideration to these factors when allocating commercial fishing licences within Zones I and II. Adjacency means adjacent to or within a reasonable geographic distance of the zone in question. The principles will be applied in such a way as to promote a fair distribution of licences between the residents of the Nunavut Settlement Area and the other residents of Canada and in a manner consistent with Canada’s interjurisdictional obligations.

Zones I and II and, in making any decision which affects Zones I and II, Government shall consider such recommendations.”

[2] For example, in 2004, and again in 2009, Canada’s Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans found that Nunavut lagged far behind the access enjoyed by Atlantic provinces, despite efforts towards a commercial purchase of licences or quota (see, e.g.: Senate of Canada, “Nunavut Marine Fisheries: Quotas and Harbours: Report of the Standing Senate committee on Fisheries and Oceans” (June 2009)).

[3] Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated v Canada (Fisheries and Oceans), 2024 FC 649 [NTI and QIA v DFO] at para 78. See also paras 66 and 103.

[4] NTI and QIA v DFO at paras 60–66.

[5] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 23.

[6] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 23.

[7] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 65.

[8] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 68.

[9] NTI and QIA v DFO at paras 66–68.

[10] NTI and QIA v DFO at paras 69–72.

[11] NTI and QIA v DFO at paras 72 and 77.

[12] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 72.

[13] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 73.

[14] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 74.

[15] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 75.

[16] NTI and QIA v DFO at para 60.