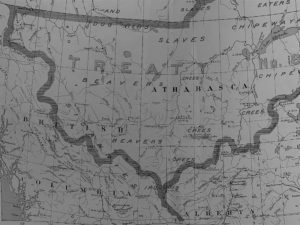

Figure 1. Appears in Treaty No. 8 and Adhesions, Reports, Etc. (June 21, 1899). Report of Commissioners for Treaty No. 8, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 22nd September, 1899.

((I am grateful for Christina Gray’s feedback and mentorship in developing this blog))

Blueberry River First Nations secured a landmark victory this summer confirming that the Crown unlawfully breached promises made to the Indigenous signatories when Treaty 8 was signed. Yahey v British Columbia confirms that large scale industrial development on Treaty 8 land in what is now northeastern British Columbia has breached Treaty 8.((Yahey v British Columbia, 2021 BCSC 1287 [Yahey].)) This is a significant case for several reasons: the BC Supreme Court’s (“the Court”) decision itself, that this decision was not appealed, and the recent agreement signed by Blueberry and BC. Taken together, this sets a precedent for understanding cumulative impacts on Treaty rights and what it takes to uphold those rights.

BC will not appeal Blueberry case

Treaty 8 leaders urged BC not to appeal the Court’s decision in order to respect its commitment to reconciliation and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. On July 28, 2021, BC released a statement declaring that it would not appeal the decision. BC defers to the Court’s direction, stating that “the Province must improve its assessment and management of the cumulative impact of industrial development on Blueberry River First Nations’ Treaty rights, and to ensure these constitutional rights are protected… The Province recognizes that negotiation, rather than litigation, is the primary forum for achieving reconciliation and the renewal of the Crown-Indigenous relationship.”

Developing an interim approach to protecting Blueberry’s way of life

In addition to granting the declarations Blueberry sought, the Court ordered that the parties must work “with diligence” to establish mechanisms that assess and manage cumulative impacts within Blueberry’s territory. This was followed by an agreement between Blueberry and the Province on October 7, 2021 which establishes a $35 million fund for Blueberry to undertake land healing activities and a $30 million fund to support Blueberry in protecting their way of life. Blueberry and the Province will finalize an interim approach for reviewing new natural resource activities balancing Treaty 8 rights, the economy, and the environment before developing long-term solutions that protect Treaty 8 rights and an “Indigenous way of life”.

Meaningfully upheld Treaty promises

Blueberry is a signatory to Treaty 8, to which Blueberry adhered in 1900. Treaty 8 is the home territory to 39 First Nations in total, encompassing approximately 840,000 kilometers across what is known today as northwestern Saskatchewan, northern Alberta, northeastern British Columbia, and the southwest part of the Northwest Territories. Similar to other First Nations Treaty signatories, Blueberry understood that signing Treaty 8 would establish a nation-to-nation relationship based on mutual benefit.

Blueberry argued that BC authorized extensive industrial development (associated with oil and gas, forestry, mining, hydroelectric infrastructure, agricultural clearing and other activities) over several decades without regard to Blueberry’s Treaty rights. Blueberry’s position is that the cumulative effects of industrial development breached the Treaty, infringed their Treaty rights, and had significant adverse impacts on the meaningful exercise of members’ Treaty rights. Cumulative effects are “changes to environmental, social and economic values caused by the combined impact of past, present, and potential future human activities and natural processes.”((Ibid at para 1587. [Yahey]))

The Court held that the provincial regulatory regimes related to oil and gas, forestry, and wildlife management were inadequate and failed to consider Treaty rights and/or cumulative effects.((Ibid at paras 1195-1197, 1564, 1662, 1710-1713)) Despite a nearly 20 year record demonstrating the “critical changes affecting Blueberry’s ability to meaningfully exercise its treaty rights” within the territory, BC failed to diligently implement Treaty 8,((Ibid at paras 1195-1197)) and failed to uphold the honour of the Crown.((Ibid at paras 1737 and 1750. The honour of the Crown “arises from the Crown’s assertion of sovereignty over Aboriginal people and de facto control of land and resources that were formerly in the control of that people and goes back to the Royal Proclamation of 1763”: Mikisew Cree First Nation v Canada (Governor General in Council), 2018 SCC 40. The purpose of the honour of the Crown is “the reconciliation of pre-existing Aboriginal societies with the assertion of Crown sovereignty”: Manitoba Metis Federation Inc v Canada (Attorney General), 2013 SCC 14. ))

The main issue

Blueberry’s main argument is that Treaty 8’s fundamental promise is that the Indigenous signatories would be able to continue their way of life based on hunting, fishing, and trapping. ((Indigenous signatories here means the First Nations who adhered to Treaty 8. It is meant to ensure consistency with the Indigenous way of life described in the Treaty but avoid replicating racist language in Treaty 8. ))

In failing to diligently and honourably implement this essential promise, BC significantly interfered with or undermined Blueberry’s way of life and thus its Treaty rights. Blueberry also argued that by not managing the use and taking up of lands within Treaty 8 territory, the Province encouraged extensive development and breached its fiduciary obligations to Blueberry.

The Court focused on whether Blueberry’s Treaty rights have been infringed by analyzing whether sufficient and appropriate land in Blueberry’s traditional territory exists for Blueberry to meaningfully exercise its Treaty rights. The Court also considered, if the Treaty rights were infringed, whether BC breached the Treaty in failing to diligently implement the promises contained within it.

Analysis

A) Treaty 8 Promises Crown will not interfere with Indigenous Way of Life

In considering whether to sign Treaty 8, Blueberry was concerned with hunting and fishing rights and wanted assurances that its way of life would continue. The Court agreed with Blueberry that Treaty 8 included a promise to continue the Indigenous signatories’ way of life. This meant that although Treaty 8 would undoubtedly bring change, completing a treaty was impossible unless it contained “assurances that hunting and fishing rights would not be curtailed and the Indigenous peoples would not be confined to reserves”.((Ibid at paras 196-197. )) Part of this promise was that the Crown would not “significantly affect or destroy the basic elements or features needed for that way of life to continue”.((Ibid at para 175. ))

Treaty 8 promises the Indigenous signatories that their way of life would not be interfered with because:

- The area covered by Treaty 8 was not suitable for farming, therefore Indigenous peoples were meant to continue with traditional hunting, fishing, and trapping pursuits;((Ibid at para 202.))

- In general, most treaties specified that lands would be completely opened up for settlement, but Treaty 8 set out options for pursuits moving forward, including farming, ranching, or continued hunting and fishing;((Ibid at para 203. ))

- During negotiations, the Indigenous people had “consistently voiced their concern about the Treaty interfering with their rights to hunt and fish. The Crown consistently reassured the Indigenous people that their way of life would be free from interference”;((Ibid at para 204))

- The correspondence and reporting surrounding Treaty 8 negotiations consistently said that limited reserve land would be needed as generally, Indigenous people in this area were more likely to hunt and fish than cultivate the land;((Ibid at para 205))

- Unlike other treaties, the text of Treaty 8 referred to the “right to pursue their usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing” instead of referring to these as avocations (which is a hobby or minor occupation); and,((Ibid at para 206. ))

- Treaty Commissioner Laird prepared a Treaty 8 explanatory document which explicitly reassured the Indigenous people that they “will be allowed to hunt and fish all over the country as they do now, subject to such laws as may be made for the protection of game and fish in the breeding season.” Commissioner Laird also reassured Indigenous people that if they chose to take the Treaty they would be just as free to hunt and fish after the Treaty as before.((Ibid at para 207. ))

The Yahey decision confirms that Treaty 8 contains a promise that the Crown would not interfere with the Indigenous signatories’ way of life. The Court also relied on prior case law that has considered Treaty 8 promises, including R v Badger, stating that “the Supreme Court of Canada has recognized that the guarantee that hunting, fishing and trapping would continue was the “essential element” that led Indigenous people to sign [Treaty 8]”.((Ibid at para 269, citing R v Badger, 1996 CanLII 236 (SCC), at paras 39 and 82.))The Court also cited West Moberly, where the BC Court of Appeal recognized Crown promises went beyond rights to hunt, fish, or trap for food. The Crown promised that “the same means of earning a livelihood would continue after [Treaty 8] as existed before it; Indigenous people would be as free to hunt and fish after the Treaty as they had been before it; and the Treaty would not lead to forced interference with their mode of life”.((Ibid at para 270, citing West Moberly First Nations v. British Columbia (Chief Inspector of Mines), 2011 BCCA 247 at para 130. ))

B) The test for infringing Treaty rights

The test for infringing Treaty rights requires a “nuanced and contextual understanding” of determining whether any meaningful right remains.((Ibid at para 515. )) This contextual understanding should consider the governmental scheme as a whole, the history of development on the lands, and the historical use and allocation of the resources and the impacts this has caused.((Ibid at para 521)) It would be “illogical and, ultimately, dishonourable to conclude that the Treaty is only infringed if the right to hunt, fish and trap in a meaningful way no longer exists.”((Ibid at para 514)) If this were the test, courts would only be able to adjudicate once a First Nation has lost its ability to exercise its rights and carry on its way of life, rendering any remedy meaningless.((Ibid at para 514. ))

In the context of this case, the appropriate standard is whether Blueberry members can hunt, fish and trap as part of a way of life that has not been meaningfully diminished.((Ibid at para 541.))The Court also gives a more robust interpretation for the test in general, noting a range of ways in which Courts have articulated the test for treaty infringement in the past – accepting that the concept of infringement encompasses everything from “any interference” to complete extinguishment (i.e. that no meaningful right remains).((Ibid at paras 526-528. ))

C) The Crown infringed Blueberry’s Treaty rights

The Court concluded that Blueberry could no longer meaningfully exercise its Treaty rights to hunt, fish, and trap because they had been “significantly and meaningfully diminished when viewed within the context of the way of life in which these rights are grounded.”((Ibid at para 1129.))Blueberry presented compelling evidence about the intimate relationship between environmental health and stability, and its members’ ability to practice their way of life.((Ibid at paras 432-433, 1129-1132. ))

Blueberry requires healthy, mature forests, robust wildlife habitats, clean water, and undisturbed access to these places to support members’ way of life. Blueberry acknowledged that impacts of development will vary, however impacts can “accumulate and converge so as to cause a breach of the substantive promise of Treaty 8.”((Ibid at para 1045-1046. )) The Court agreed, finding that the scale of development “is fundamentally not what was agreed to at Treaty”.((Ibid at para 1077.))Further, BC’s regulatory regimes related to oil and gas, forestry, and wildlife management were inadequate and failed to consider Treaty rights and/or cumulative effects.((Ibid at paras 1195-1197, 1564, 1662, 1710-1713.)) The Court highlighted a persistent problem in Provincial decision-making: one decision-maker points to another decision-maker to consider Treaty rights and cumulative effects, when in reality, no Crown agents were doing so.((Ibid at para 1456. ))

Blueberry’s Treaty 8 rights were infringed “due to the level of “taking up” caused by provincially-authorized activities, including resulting disturbance, the impact on the wildlife, and the evidence of Blueberry members that there are not sufficient and appropriate lands in Blueberry’s traditional territories to permit the meaningful exercise of their Treaty rights.”((Ibid at paras 1131-1132. ))Despite an extensive record demonstrating the “critical changes affecting Blueberry’s ability to meaningfully exercise its treaty rights” within the territory, BC failed to diligently implement Treaty 8,((Ibid at paras 1195-1197. )) and failed to uphold the honour of the Crown.((Ibid at paras 1737 and 1750. ))

Conclusion

The Yahey decision confirms that Treaty 8 protects Blueberry’s way of life from forced interference including their rights to hunt, trap, and fish within their territory. While BC has a broad power to take up lands under Treaty 8 (meaning that the Crown can use land for “settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes” as “required”), this power is not infinite. As such, BC may not take up so much land that Blueberry can no longer meaningfully exercise its rights to hunt, trap, and fish.

Blueberry members can no longer exercise their Treaty rights as they used to, access to hunting, fishing, and trapping places within their territory is scarce or impossible, and wildlife habitat is fragmented, polluted, or nonexistent. The wildlife necessary to support this relationship are not as healthy or abundant. Blueberry members no longer peacefully enjoy time on their traplines or in hunting areas, or feel safe or welcomed in their territory. By authorizing extensive industrial development over a number of years in Blueberry’s territory and failing to consider these cumulative impacts of this development, the Province unjustifiably breached Treaty 8.

In the new agreement, Blueberry and BC hope to heal the land through restoration and rebuild Blueberry’s cultural footprint on the land. While the path forward remains tenuous, BC has agreed to “defer” 20 of 215 already-issued industrial permits, all located in areas with high cultural value. This shows some promise for a future where consent-based relationships exist between the Crown and Indigenous rights holders.